Abstract

-

Purpose

This systematic review examined the impact of generative artificial intelligence (AI) on nurses' clinical decision-making.

-

Methods

Following PRISMA guidelines, we searched four databases for empirical studies (2000-2025) examining generative AI in nursing decision-making. Two reviewers independently conducted study selection and quality assessment.

-

Results

Twenty-three studies were included (simulation studies n=7, cross-sectional n=4, qualitative n=3, implementation n=3, retrospective evaluation n=3, observational comparison n=3, experimental n=2). Large language models, particularly ChatGPT and GPT-4, were most commonly examined. Benefits included 11.3-fold faster response times, high diagnostic appropriateness (94%–98%) in neonatal intensive care, improved emergency triage agreement (Cohen's κ, 0.899-0.902), and documentation time reductions (35% to >99%). Challenges included limitations in therapeutic reliability, hallucinations in vital sign processing, demographic biases, and over-reliance risks (only 34% high trust reported).

-

Conclusion

Generative AI shows promise for augmenting nursing decision-making with appropriate oversight, though evidence is limited by predominance of simulation studies and insufficient patient-level outcome data. AI literacy integration in nursing education and robust institutional governance is essential before routine deployment. Large-scale randomized controlled trials are needed.

-

Key Words: Artificial intelligence; Clinical decision-making; Nursing informatics; Patient safety; Technology assessment

INTRODUCTION

The rapid advancement of generative artificial intelligence (AI) technologies has created unprecedented opportunities for transforming healthcare delivery and nursing practice [

1,

2]. Generative AI refers to AI systems capable of creating new content, including text, clinical recommendations, and diagnostic insights, based on patterns learned from vast datasets [

3]. Unlike traditional rule-based clinical decision support systems, generative AI—particularly large language models (LLMs) such as ChatGPT and GPT-4—can process natural language, synthesize complex clinical information, and generate contextually appropriate responses in real-time [

4,

5].

Nurses are at the forefront of healthcare delivery, making critical clinical decisions that directly impact patient safety and outcomes [

6]. Clinical decision-making in nursing involves complex cognitive processes including assessment, diagnosis, planning, implementation, and evaluation across diverse patient populations and care settings [

7]. The integration of generative AI into nursing workflows has the potential to transform these decision-making processes by providing rapid information synthesis, diagnostic support, treatment recommendations, and documentation assistance [

8,

9].

However, the novelty of generative AI technologies and their rapid deployment in clinical settings raise important questions about their impact on nursing judgment, patient safety, professional autonomy, and accountability [

10,

11]. Concerns have emerged regarding AI-generated errors (hallucinations), bias, over-reliance, therapeutic safety, and the potential erosion of clinical expertise [

12,

13]. Furthermore, the lack of clear governance frameworks, regulatory oversight, and liability structures creates uncertainty about the appropriate role of generative AI in nursing practice [

14,

15].

As healthcare systems worldwide face increasing pressures from workforce shortages, documentation burdens, and increasingly complex patient needs, understanding the role of generative AI in supporting nursing decision-making has become critically important [

16]. The Korean healthcare context, characterized by high patient-to-nurse ratios and intensive care demands, makes this topic particularly relevant for Korean nursing administrators and policymakers [

17]. Despite growing interest and implementation, the evidence base regarding generative AI's impact on nursing decision-making remains fragmented across various study designs, clinical settings, and AI technologies [

18].

While several systematic reviews have examined AI applications in nursing practice [

19,

20], these reviews predominantly focus on traditional AI systems, machine learning algorithms, and rule-based clinical decision support without distinguishing the unique characteristics of generative AI technologies. Existing reviews have not adequately addressed the specific capabilities and risks inherent to LLMs, such as hallucination generation, prompt-dependent bias amplification, and uncertainty communication challenges. Furthermore, most prior reviews cover literature published before the widespread deployment of ChatGPT and GPT-4 in late 2022 and 2023, missing the rapid evolution and real-world implementation experiences that have emerged since. Additionally, existing reviews often examine general technology adoption or AI applications broadly, rather than focusing specifically on the impact on nurses' clinical decision-making processes—a critical gap given that decision-making is central to nursing practice and patient safety. Therefore, a systematic review specifically focused on generative AI's impact on nursing decision-making, incorporating the most recent evidence and addressing the unique characteristics of these technologies, is essential to inform safe and effective implementation in clinical practice.

A comprehensive systematic review is needed to synthesize empirical evidence, identify benefits and risks, and inform evidence-based policies, educational curricula, and implementation strategies that maximize benefits while rigorously managing risks [

21]. This systematic review aims to (1) examine the specific aspects of nursing decision-making impacted by generative AI, (2) identify the types of generative AI technologies being used or studied in nursing practice, (3) evaluate the reported benefits and positive impacts on nursing decision-making, (4) identify the challenges, limitations, and risks associated with generative AI use, and (5) discuss implications for nursing practice, education, and policy.

METHODS

Study Design

This systematic review was conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines [

22]. A detailed review protocol was developed a priori, including predefined research questions, search strategies, inclusion/exclusion criteria, data extraction procedures, and quality assessment methods. However, the protocol was not prospectively registered in a public database such as PROSPERO or Open Science Framework. This limitation is acknowledged in the Discussion section. The PRISMA 2020 checklist is provided in

Supplementary Material 1.

A comprehensive literature search was conducted in November 2025 using four electronic databases: PubMed/Medline, Web of Science, CINAHL, and Google Scholar. The search covered publications from January 2000 to November 2025 to reflect the emergence of generative AI in healthcare. The search strategy was developed with input from a health sciences librarian and included MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) terms and keywords related to three domains: generative AI (e.g., "generative artificial intelligence," "large language model," "ChatGPT," "GPT-4"), nursing (e.g., "nursing practice," "registered nurse," "nursing staff"), and clinical decision-making (e.g., "decision making," "clinical reasoning," "decision support"). Search terms were adapted for each database to accommodate indexing differences, including MeSH for PubMed and subject headings for CINAHL. Reference lists of included studies and relevant reviews were manually screened, and citation tracking in Google Scholar was performed to identify additional eligible studies. Grey literature from major nursing organizations, including the American Nurses Association, International Council of Nurses, and Korean Nurses Association, was reviewed to inform search strategy development and provide contextual understanding of professional guidance on AI in nursing practice. However, grey literature sources were not included in the systematic review's data extraction or synthesis, as the review focused exclusively on peer-reviewed empirical research meeting the predefined inclusion criteria. The detailed search strategy is presented in

Supplementary Material 2.

Studies were included if they were empirical investigations examining the use of generative AI in nursing practice and its impact on nurses' clinical decision-making. Eligible study designs included quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-methods research, such as experimental studies, observational studies, simulation-based evaluations, pilot studies, and qualitative explorations. Studies were required to involve registered nurses, nurse practitioners, or clinical nurses working in real clinical environments or simulated decision-making scenarios. Only peer-reviewed empirical research articles published in English in indexed academic journals were included. Grey literature, including organizational reports, position statements, technical documents, and white papers, was excluded from data extraction and synthesis but was consulted during search strategy development to ensure comprehensive coverage of relevant terminology and concepts.

Studies were excluded if they were reviews, bibliometric analyses, theoretical discussions, policy papers, or opinion pieces without empirical data. Editorials, commentaries, and conference abstracts were excluded due to lack of methodological rigor. Studies focusing solely on traditional or rule-based AI rather than generative AI were excluded, as were those examining AI in nursing education without clinical practice relevance. Research involving only nursing students or studies addressing general technology adoption without decision-making outcomes were excluded. Duplicate publications, secondary analyses without new findings, and non-English papers were also excluded. Studies published in languages other than English were excluded due to resource constraints, which may introduce language bias. This limitation is discussed further in the Discussion section.

Study Selection Process

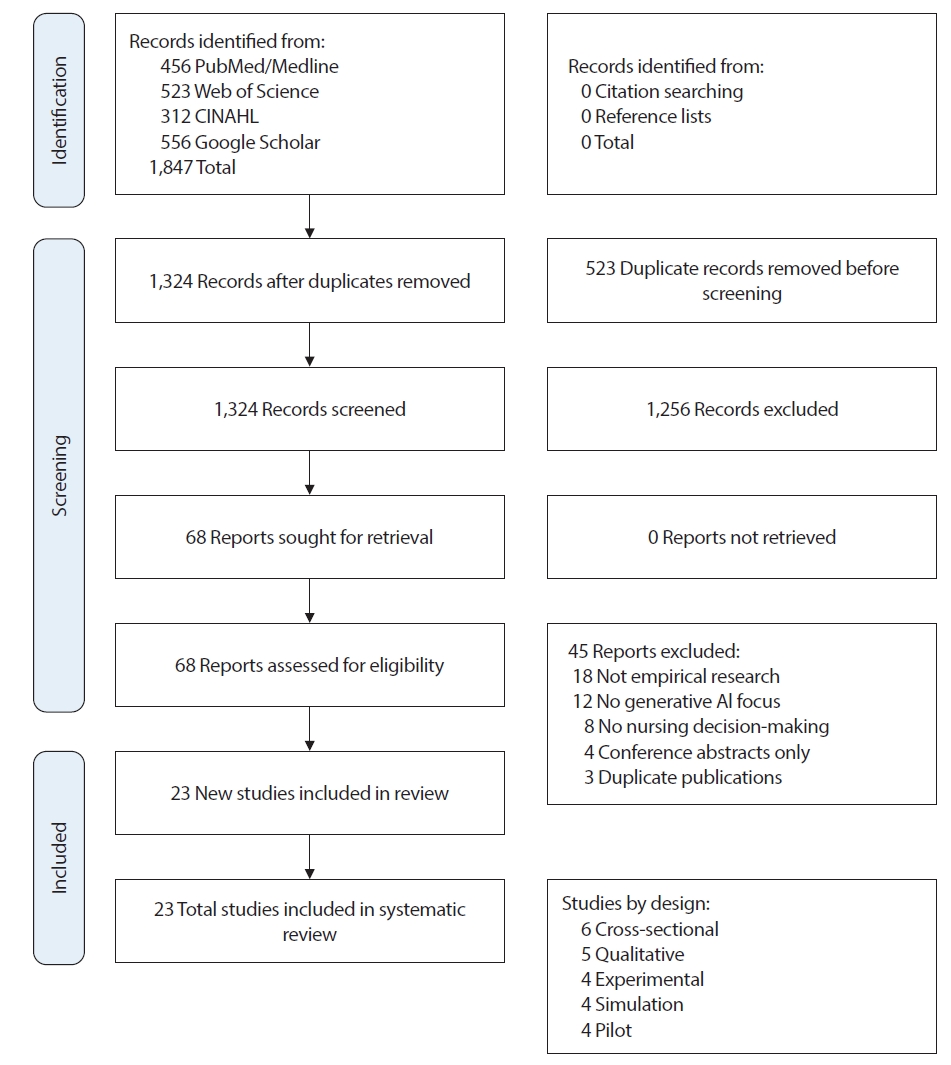

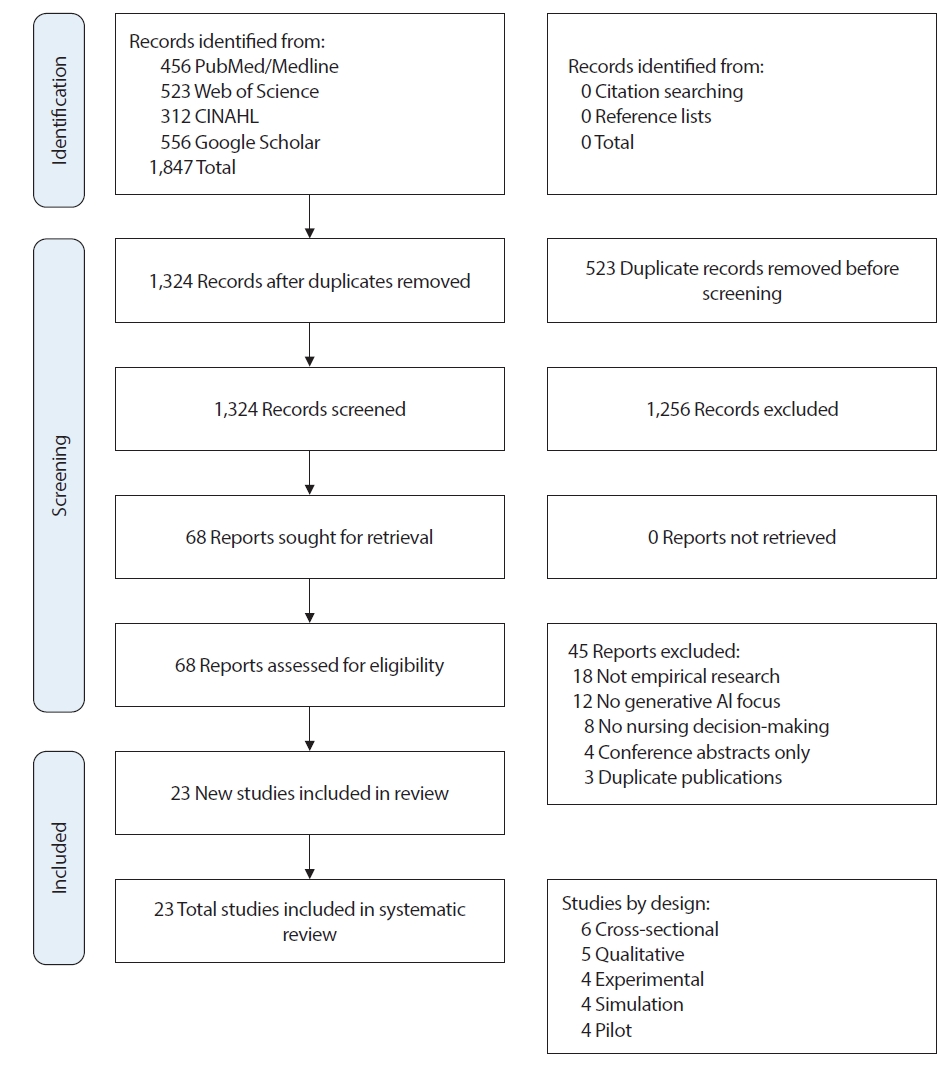

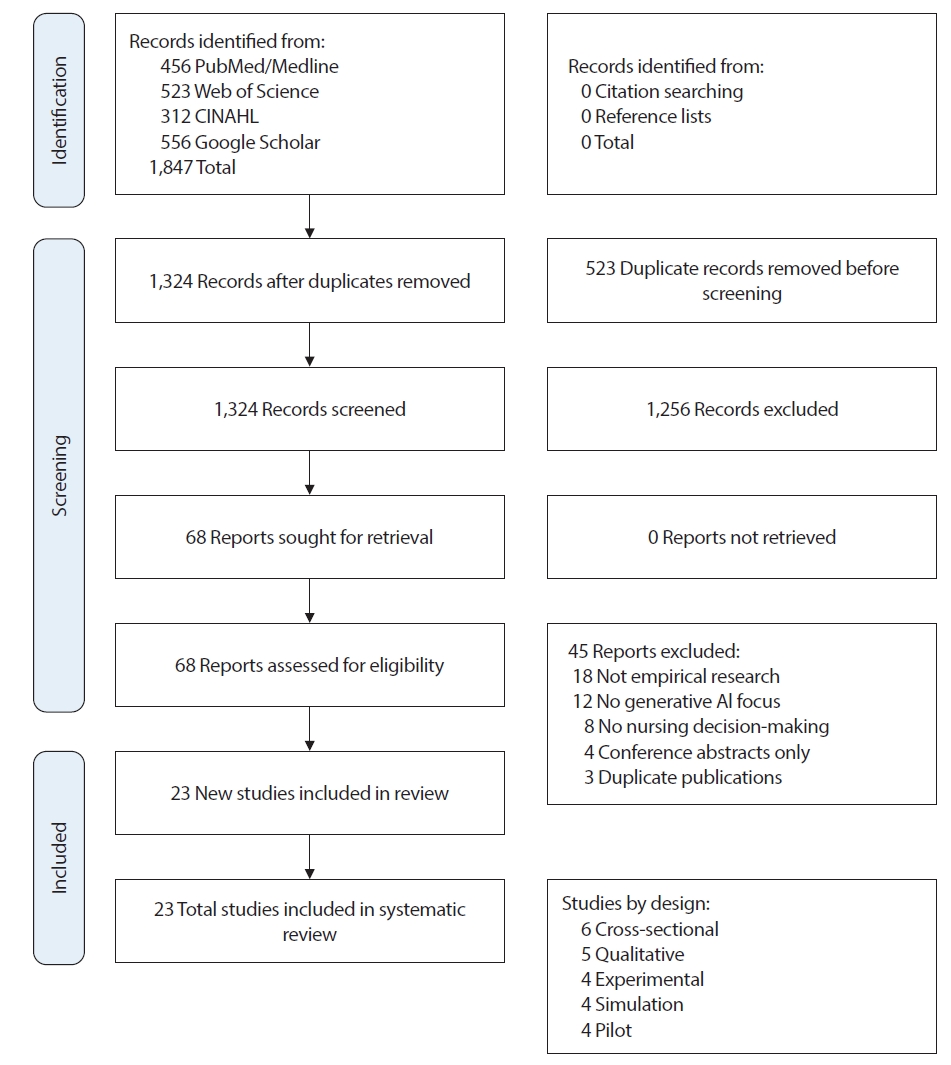

Study selection was conducted in two stages by two independent authors following a standardized protocol. In the first stage, both reviewers independently screened all titles and abstracts of the 1,324 unique records identified after duplicate removal, using the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Disagreements that arose at this stage were resolved through discussion, ultimately leading to a final consensus. This process resulted in 68 studies proceeding to full-text review. In the second stage, both reviewers independently assessed the full texts of all 68 articles for eligibility. Each reviewer documented the reasons for exclusion for studies that did not meet inclusion criteria. Again, disagreements were resolved through discussion and third-party adjudication when necessary. The inter-rater agreement for full-text screening was substantial (Cohen's kappa=0.82), indicating high consistency between reviewers. This dual independent review process resulted in 23 studies being included in the final synthesis (

Appendix 1). The study selection process is documented in the PRISMA flow diagram (

Figure 1). Data on study selection agreement are provided in

Supplementary Material 3.

Data extraction was conducted independently by two reviewers (MK and SDK) using a standardized extraction form developed for this review, with discrepancies resolved through consensus and third-party adjudication when required. Extracted study information included author, publication year, country, study design, methodology, sample size, participant characteristics, and clinical setting (e.g., intensive care unit [ICU], emergency department [ED], neonatal ICU, long-term care).

Generative AI characteristics included the AI type (e.g., ChatGPT, GPT-4, custom LLM, hybrid system), system architecture and features, and implementation approach (autonomous vs. human-supervised). Decision-making characteristics captured domains assessed (e.g., assessment, diagnosis, treatment, documentation, education) and specific clinical tasks or scenarios evaluated. Outcome data included outcome measures, assessment tools, quantitative findings (e.g., percentages, means, effect sizes), qualitative results (themes, representative quotes), reported benefits, challenges, and risks. Quality appraisal included documented study limitations, funding sources, and potential conflicts of interest.

Quality Assessment

The methodological quality of included studies was assessed using appropriate tools based on study design to ensure rigorous evaluation across diverse methodologies. Randomized controlled trials were assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool 2 (RoB 2) [

23]. Non-randomized experimental studies were evaluated using the Risk of Bias in Non-randomized Studies of Interventions (ROBINS-I) [

24]. Cross-sectional and observational studies were assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) [

25]. Qualitative studies were evaluated using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) Qualitative Checklist [

26].

Due to substantial heterogeneity in study designs, AI technologies, clinical settings, and outcome measures, a narrative synthesis approach was employed following guidance from the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination [

27]. Meta-analysis was not feasible due to this heterogeneity, which precluded meaningful statistical pooling of results.

As this study was a systematic review of published literature, it did not involve human subjects and therefore did not require institutional review board approval. All included studies were published research available in the public domain, ensuring that our review adhered to ethical standards for secondary research.

RESULTS

Study Selection

The database search identified 1,847 records across PubMed/Medline (n=456), Web of Science (n=523), CINAHL (n=312), and Google Scholar (n=556). After removing 523 duplicates, 1,324 unique records were screened by title and abstract, resulting in the exclusion of 1,256 studies that did not meet inclusion criteria—primarily because they were not focused on generative AI (n=456), were not related to nursing (n=389), did not examine decision-making (n=278), or were not empirical research (n=133). This left 68 articles for full-text review. During full-text assessment, 45 articles were excluded due to being reviews (n=18), theoretical or policy papers (n=14), bibliometric studies (n=3), lacking a generative AI focus (n=6), not addressing nursing decision-making (n=3), or being a non–peer-reviewed conference abstract (n=1). Ultimately, 23 empirical studies satisfied all eligibility criteria and were included in the final synthesis, as summarized in the PRISMA 2020 flow diagram (

Figure 1). All 23 included studies were peer-reviewed empirical research articles published in indexed academic journals; no grey literature sources met the inclusion criteria for data extraction and synthesis. Of the 23 included studies, 21 (91%) were peer-reviewed journal articles published in indexed academic journals, and 2 (9%) were widely cited preprints or arXiv papers that met our quality criteria and provided valuable contributions to the emerging evidence base. No other grey literature sources (e.g., organizational reports, white papers, conference proceedings) met the inclusion criteria for data extraction and synthesis. A detailed list of the included studies is presented in

Supplementary Material 3

Study characteristics are summarized in

Table 1. The 23 included studies were published between 2020 and 2025, with most (n=12) appearing in 2024 (52%), appearing in 2024 (52%), followed by 2025 (n=8, 35%), 2023 (n=2, 9%), and 2020 (n=1, 4%), reflecting rapidly increasing scholarly attention to generative AI in nursing. Research was conducted globally, with Israel contributing the largest number of studies (n=4, 17%), followed by Taiwan (n=4, 17%), multi-national studies (n=5, 22%), South Korea (n=2, 9%), USA (n=2, 9%), and Germany (n=2, 9%). Additional individual studies originated from Saudi Arabia, Hong Kong, Turkey, and Australia, indicating broad international engagement. The included studies applied varied research methodologies, including experimental or pilot evaluations, simulation-based studies, cross-sectional research, and qualitative designs. Sample sizes ranged widely depending on study type and purpose. from 10 nurse leaders to 312 nurses in participant-based studies, and 45 to 2,000 cases in vignette or retrospective dataset evaluations. Clinical settings also varied, with research conducted in high-acuity environments such as intensive care units (n=7, 30%) and emergency departments (n=9, 39%), as well as general hospital settings (n=4). Additional settings included community/home health nursing (n=2, 9%) and oncology nursing (n=1, 4%). Participants represented multiple nursing roles, including registered nurses, advanced practice nurses, ICU and emergency nurses, and nurse administrators, supporting applicability across diverse clinical contexts.

The included studies employed diverse generative AI technologies, reflecting the heterogeneous and rapidly evolving landscape of AI in healthcare. ChatGPT/GPT-4 and other commercial LLMs were used in 14 studies (61%), multiple LLMs compared across studies in 4 studies (17%), retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) systems in 2 studies (9%), voice-based or automated documentation systems in 2 studies (9%), and other specialized LLM architectures in 1 study (4%). This technological diversity reflects the real-world implementation environment where generative AI is often integrated with existing clinical decision support infrastructure rather than deployed as standalone systems.

Quality Assessment

The quality assessment results are summarized in

Table 2. Overall, the included studies demonstrated moderate to high methodological quality, although quality varied by study design. The experimental studies generally showed low to moderate risk of bias, with appropriate use of objective outcome measures, though blinding was inconsistently applied. Cross-sectional studies received strong ratings on the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (scores 6–8/9), although several lacked justification for sample size. Qualitative studies demonstrated strong methodological rigor, including transparent analytic procedures and reflexivity. Simulation studies showed adequate design validity with clinically realistic scenarios, but limited generalizability to real-world practice. Implementation and demonstration studies provided valuable feasibility and preliminary outcome data but were constrained by small samples, limited controlled comparisons, and short follow-up periods. Common methodological limitations across studies included small sample sizes, single-site recruitment, limited longitudinal outcome measurement, and insufficient reporting of patient-level impact. Despite these limitations, the overall evidence base offers sufficient methodological strength to inform preliminary conclusions about the role of generative AI in nursing decision-making. It is important to note that the evidence base comprises studies with varying levels of evidence strength. Experimental studies (n=4) and randomized controlled trials (n=2) provide higher-level evidence for causal inferences, while cross-sectional studies (n=6), simulation studies (n=4), and pilot studies (n=4) offer preliminary or exploratory evidence. Qualitative studies (n=5) provide important insights into implementation experiences and contextual factors but do not establish effectiveness. This heterogeneity in study designs means that findings should be interpreted with consideration of the strength and certainty of evidence for each specific outcome or application domain. Meta-analysis was not feasible due to this heterogeneity, and our synthesis reflects the current state of an emerging field where high-quality experimental evidence is still accumulating.

Generative AI technologies demonstrated meaningful impacts on nursing practice across multiple clinical domains, as summarized in

Table 3. Commercial large language models, such as ChatGPT, significantly improved response time in clinical assessment and triage, operating over ten times faster than expert nurses, though initial assessments showed variable appropriateness and occasional unnecessary test recommendations. Domain-specific fine-tuned models achieved high diagnostic accuracy rates of 94%–98% in neonatal intensive care settings, with Claude-2.0 outperforming ChatGPT-4 in both accuracy and speed. However, therapeutic recommendations remained less reliable, with concerns about potentially harmful suggestions and critical omissions.

Retrieval-augmented generation systems demonstrated substantial improvements in emergency triage decision-making, achieving high agreement scores (quadratic weighted kappa 0.902) and accuracy (0.802), along with reduced over-triage and improved consistency. Multiple emergency department triage studies showed high agreement between AI and clinician assessments (Cohen's κ ranging from 0.899 to 0.902), though some noted AI's tendency toward overestimation of severity. Voice-based information and documentation systems completed standardized ICU tasks significantly faster than traditional methods and produced significantly fewer errors.

AI-assisted documentation systems demonstrated dramatic time savings, with documentation time reduced from approximately 15 to 5 minutes per patient in one study and greater than 99% time reduction in another multi-hospital implementation, while maintaining accuracy. A longitudinal study showed that automated data entry reduced errors from approximately 20% to 0% and substantially reduced data transfer times, with improved nurse job satisfaction. Simulation studies demonstrated diagnostic synergies between AI and nurses, particularly in identifying rare conditions, highlighting the importance of human-AI collaboration.

Despite these benefits, several risks and limitations were identified. A diagnostic-therapeutic performance gap remained evident, with AI systems achieving 94%–98% appropriateness for diagnostic recommendations but demonstrating limitations in therapeutic recommendations. Occasional hallucinations were observed in outputs, particularly when processing vital sign inputs. Demographic biases in recommendations based on patient characteristics and severity factors were noted. Automation bias and over-reliance issues emerged, with studies reporting that higher AI-CDSS reliance correlated with lower decision regret, though trust calibration issues remained.

Institutional readiness was limited, with unclear governance structures, liability uncertainty, and inconsistent deployment policies. Qualitative studies revealed concerns about trust, with only 34% of NICU nurses reporting high trust in one study. Nurses expressed concerns about liability, accountability, fear of deskilling, and evolving role boundaries. Training gaps were significant, with only 15% of nurses reporting formal AI education and only 33% feeling prepared, though 89% expressed interest in further training. Implementation challenges included initial learning curves, technical glitches, resistance to workflow changes, connectivity issues in home settings, and limited offline functionality. Overall, generative AI shows potential to enhance nursing decision-making, efficiency, and workflow when accompanied by appropriate clinical oversight, structured training, and governance frameworks, while mitigating risks related to patient safety, equity, and professional accountability.

DISCUSSION

This systematic review synthesized evidence from 23 empirical studies examining generative AI use and its impact on nurses' clinical decision-making. Generative AI technologies show preliminary evidence of potential to enhance efficiency, diagnostic reasoning, and documentation, though the certainty of this evidence varies across application domains and is limited by the predominance of implementation studies, simulations, and small-scale evaluations. Notable limitations and safety concerns were also identified across multiple studies. Commercial LLMs, such as ChatGPT, provided rapid responses in clinical scenarios, with a mean response time of 45 seconds compared to 8.5 minutes for expert nurses, representing an 11.3-fold speed advantage [

28]. However, they showed indecisiveness in initial assessments, with appropriateness scores 29% lower than those of expert nurses, and recommended 35% more unnecessary diagnostic tests, indicating a tendency toward over-conservative decision-making [

28]. Domain-specific, fine-tuned LLMs achieved high diagnostic appropriateness rates of 94%–98% in neonatal intensive care settings, with Claude-2.0 outperforming ChatGPT-4 in both accuracy and speed [

29]. Retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) systems demonstrated substantial improvements in emergency triage decision-making, with improved agreement (quadratic weighted kappa [QWK] 0.902) and accuracy (0.802), along with reduced over-triage and improved consistency [

30,

31]. Multiple studies of emergency department triage showed high agreement between AI and clinician assessments (Cohen's κ ranging from 0.899 to 0.902), though some studies noted AI's tendency toward overestimation of severity [

32,

33]. Voice-based information and documentation systems completed standardized ICU tasks significantly faster than traditional patient data management systems and paper methods, and produced significantly fewer errors [

34]. AI-assisted documentation systems demonstrated dramatic time savings, with documentation time reduced from approximately 15 to 5 minutes per patient in one study [

35] and greater than 99% documentation time reduction reported in another multi-hospital implementation [

36], while maintaining documentation accuracy. One longitudinal study from 2020 showed that automated data entry reduced errors from approximately 20% to 0% and substantially reduced data transfer times (from 5 minutes to 2 hours per event), with improved nurse job satisfaction [

37]. Despite these benefits, the diagnostic-therapeutic performance gap remains a critical challenge. AI systems achieved 94%–98% appropriateness for diagnostic recommendations but demonstrated limitations in diagnostic specificity and therapeutic recommendations, with concerns about potentially harmful suggestions and critical omissions [

29]. This gap reflects the difficulty AI systems face in integrating patient-specific factors, comorbidities, contraindications, medication interactions, and nuanced risk-benefit assessments required for therapeutic decisions. Simulation studies demonstrated diagnostic synergies between AI and nurses, particularly in identifying rare conditions, highlighting the importance of human-AI collaboration [

38,

39]. High AI trust without adequate scrutiny led to automation bias, a phenomenon well-documented in the broader automation literature [

40-

42]; studies reported that higher AI-CDSS reliance correlated with lower decision regret, though trust calibration issues remain [

43]. Occasional hallucinations were observed in LLM outputs, particularly when processing vital sign inputs [

36], and demographic biases in recommendations based on demographic and severity factors were observed [

44]. These findings emphasize the need for rigorous oversight, policy guidance, and structured education to ensure safe and equitable AI use.

Generative AI can enhance nursing practice when implemented with appropriate supervision. Lower-risk applications include documentation assistance, triage support, and clinical information retrieval, all of which benefit efficiency without compromising safety [

34-

37]. More direct clinical decision support, such as diagnostic and therapeutic recommendations, requires strict human oversight, local validation, and clear accountability structures [

45,

46]. AI literacy should be integrated into nursing education at all levels. Foundational education should cover basic AI concepts, capabilities, limitations, ethical considerations, and professional accountability [

47]. Intermediate training should focus on critical evaluation, integration into clinical reasoning, and avoidance of automation bias [

40-

42], while advanced training should encompass AI system evaluation, implementation planning, governance, and policy advocacy [

48]. Simulation exercises and continuing education programs are recommended to reinforce practical application skills and critical evaluation [

38,

39]. Administrators should establish institutional AI committees with strong nursing representation to oversee AI deployment and ensure safe integration into clinical workflows [

46,

48]. Policies must define acceptable AI uses, prohibited applications, and accountability frameworks. Mandatory incident reporting, regular performance monitoring, and bias audits are essential. Local validation and continuous staff training are required, with protocols for rapid system suspension if safety concerns arise. Regulatory engagement and alignment with national health information strategies can facilitate safe, contextually appropriate AI implementation. Research priorities include addressing the diagnostic-therapeutic gap, evaluating patient-centered outcomes, optimizing supervision, monitoring demographic biases, assessing long-term impacts on clinical reasoning, and conducting comprehensive economic evaluations [

19,

20]. Large-scale, multi-site randomized controlled trials with standardized outcome measures and longer follow-up periods are recommended to strengthen the evidence base. In the Korean nursing context, high patient-to-nurse ratios, intensive care demands, advanced health information technology infrastructure, and emphasis on quality and safety support generative AI adoption. Hospitals should leverage existing electronic health records, utilize AI-assisted documentation to mitigate workforce pressures, develop Korean language models, conduct local validation, and capitalize on nursing informatics expertise to lead AI evaluation and implementation. Korean language adaptation has shown promise, with studies demonstrating the feasibility of Korean Triage and Acuity Scale (KTAS)-based systems and high accuracy in real-world Korean emergency department conversations [

31]. Overall, the evidence suggests that while generative AI holds promise for enhancing nursing practice, its safe and effective use requires structured human oversight, robust education, careful policy planning, and ongoing monitoring to mitigate risks and optimize patient outcomes.

The strength of evidence varies across different applications of generative AI in nursing practice. Strong evidence (from multiple convergent studies) supports efficiency improvements in documentation. Moderate evidence (from implementation studies and simulations with consistent findings) suggests potential benefits for diagnostic support and triage in controlled settings. Weak or preliminary evidence (from single studies or qualitative research) exists for therapeutic recommendations, bias mitigation, and long-term impacts on clinical reasoning. Insufficient evidence currently exists for patient-level outcomes such as mortality, hospital length of stay, or adverse event rates. Several potential sources of bias and limitations should be acknowledged. First, the lack of prospective protocol registration limits the transparency and reproducibility of our review process. While we developed and followed a detailed a priori protocol throughout the review, the absence of public registration means that protocol deviations, if any, cannot be independently verified. This may increase the risk of selection bias and post-hoc decision-making, although we attempted to minimize this through rigorous dual independent review processes and comprehensive documentation of all methodological decisions. Second, the technological heterogeneity among included studies presents challenges for interpretation and generalizability. While we established clear operational definitions for "generative AI" (see Methods, Section 3), the included studies employed diverse AI architectures ranging from pure LLMs to hybrid systems integrating generative and rule-based components. This heterogeneity reflects the real-world implementation environment but complicates direct comparisons of effectiveness and safety across studies. Different system architectures may have different risk-benefit profiles, and our findings should be interpreted with consideration of this technological diversity. Future reviews may benefit from subgroup analyses based on specific AI architectures once sufficient evidence accumulates for each category. Third, the heterogeneity in study designs and evidence levels limits the certainty and generalizability of our findings. The evidence base comprises predominantly implementation/demonstration studies (n=3), simulation studies (n=7), cross-sectional studies (n=4), and qualitative studies (n=3), with only a small number of experimental studies (n=2) and observational comparison studies (n=3). Retrospective evaluation studies (n=3) provided valuable real-world performance data but are limited in establishing causality. This means that many findings are based on preliminary or exploratory evidence rather than definitive effectiveness trials; simulation-based findings may not translate to real-world clinical performance; small sample sizes and short follow-up periods limit statistical power and long-term outcome assessment; the predominance of single-site studies limits external validity; and few studies measured patient-level outcomes, focusing instead on process measures or surrogate endpoints. Therefore, our conclusions should be interpreted as describing the current state of an emerging field rather than definitive evidence of effectiveness. Statements about "benefits" or "improvements" reflect findings from available studies but should not be interpreted as established effects until confirmed by larger, multi-site randomized controlled trials with patient-centered outcomes and longer follow-up periods. The strength of evidence varies substantially across different applications and outcomes, with stronger evidence for efficiency gains (e.g., documentation time) and weaker evidence for clinical outcomes (e.g., patient safety, diagnostic accuracy in real-world settings). Fourth, by restricting inclusion to English-language publications, we may have missed relevant studies published in other languages, particularly from non-English-speaking countries where generative AI implementation may differ. This language restriction could introduce language bias and limit the generalizability of our findings to non-English-speaking contexts. Fifth, by including only peer-reviewed journal articles and excluding grey literature and conference proceedings, we may have introduced publication bias, as studies with negative or null findings are less likely to be published in peer-reviewed journals. While we included two widely cited preprints/arXiv papers [

30,

31] that met our quality criteria, given the rapidly evolving nature of generative AI, important findings may exist in preprint servers (e.g., arXiv, medRxiv) or technical reports that were not captured in our review. Despite these limitations, this review provides the first comprehensive synthesis of generative AI's impact on nursing decision-making and offers important guidance for safe implementation, while clearly delineating the preliminary nature of much of the current evidence base.

CONCLUSIONS

This systematic review of 23 studies demonstrates that generative AI, particularly LLMs, can enhance nursing practice by improving diagnostic accuracy, increasing response speed, and streamlining workflow efficiency. However, risks remain, including therapeutic reliability gaps, hallucinations, demographic bias, and insufficient governance structures. Current evidence supports supervised human–AI collaboration rather than autonomous decision-making, with staged implementation focusing first on low-risk applications such as documentation support and triage assistance. Strengthening AI literacy through structured education and competency-based training, along with clear governance, monitoring, and accountability frameworks, will be essential for safe adoption. Future research should address safety validation, long-term clinical effectiveness, bias mitigation, implementation strategies, and cost-effectiveness using standardized and multi-site methodologies. In Korea, linguistic adaptation, contextual validation, and policy alignment will be required for successful integration. Generative AI holds promise to augment nursing judgment and improve care quality, but responsible adoption will require coordinated efforts across clinical, educational, administrative, and policy domains.

Article Information

-

Author contributions

Conceptualization: MK, SDK. Methodology: MK, SDK. Formal analysis: MK, SDK. Data curation: MK, SDK. Visualization: KSD. Project administration: KSD. Writing - original draft: KMJ. Writing - review & editing: KSD. All authors read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest

None.

-

Funding

None.

-

Data availability

Please contact the corresponding author for data availability.

-

Acknowledgments

None.

Supplemental materials

Figure 1.Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 flow diagram of study selection process for the systematic review on generative artificial intelligence (AI) use and its impact on nurses’ clinical decision-making. The diagram illustrates the number of records identified, screened, assessed for eligibility, and included in the review, along with reasons for exclusion at the full-text stage.

Table 1.Summary of the Characteristics of the Included Studies (N=23)

|

Study No. |

Author (year) |

Country |

Study design |

Participants |

Setting |

AI technology |

Key outcomes |

|

[A1] |

Saban and Dubovi (2025) |

Israel |

Cross-sectional vignette study |

68 (30 Expert nurses, 38 nursing students) |

Emergency department (simulated vignettes) |

ChatGPT (GPT-3.5); clinical vignettes; diagnostic accuracy assessment |

Diagnostic accuracy, response time, clinical reasoning quality, comparison with expert performance |

|

[A2] |

Levin et al. (2024) |

Israel |

Multi-center cross-sectional evaluation |

32 Neonatal ICU nurses |

Neonatal intensive care unit |

ChatGPT-4 and Claude-2.0; NICU clinical scenarios |

Diagnostic appropriateness (94%), therapeutic appropriateness, safety assessment, completeness of recommendations |

|

[A3] |

Wong and Wong (2025) |

Hong Kong |

Retrospective evaluation study |

236 Real clinical triage records |

Emergency triage |

Retrieval-augmented generation system (MECR-RAG using DeepSeek-V3) |

Improved agreement (QWK 0.902), accuracy (0.802), reduced over-triage, improved consistency |

|

[A4] |

Lee et al. (2025) |

South Korea |

Retrospective multimetric evaluation |

1,057 Triage cases |

Emergency department (3 tertiary hospitals) |

Multiple commercial LLMs (GPT-4o, GPT-4.1, Gemini, DeepSeek V3/R1) |

Model performance varied; Gemini 2.5 flash highest accuracy (73.8%); few-shot prompting improved performance |

|

[A5] |

Gaber et al. (2025) |

China |

Benchmarking study |

2,000 Medical cases (MIMIC dataset) |

Emergency department (retrospective dataset) |

Multiple LLMs and LLM workflow with RAG |

RAG workflow improved reliability of triage/referral/diagnosis outputs compared to prompt-only LLMs |

|

[A6] |

Levin et al. (2024) |

Israel |

Simulation study |

32 ICU nurses |

Intensive care unit (simulation) |

Generative AI models (multiple LLM types); high-fidelity simulation cases |

Diagnostic synergies, differences across model types and nurse responses, rare condition identification |

|

[A7] |

Chen et al. (2024) |

USA |

Prospective evaluation and EHR analysis |

EHR datasets and healthcare worker assessments |

Clinical assistant tasks and EHR classification |

ChatGPT and GPT-4 variants |

High performance (up to 96% F1) in classification tasks; issues with incorrect statements and privacy concerns |

|

[A8] |

Alruwaili et al. (2025) |

Israel |

Cross-sectional comparative evaluation |

32 NICU nurses (5–10-year experience) |

Neonatal intensive care unit |

ChatGPT-4 and Claude-2.0; NICU scenarios |

Both models demonstrated clinical reasoning; Claude-2.0 outperformed ChatGPT-4 in accuracy and speed |

|

[A9] |

Peine et al. (2023) |

USA |

Comparative evaluation |

1 |

1,000 ED triage cases |

Emergency department |

ChatGPT-4; ESI |

|

[A10] |

Haim et al. (2024) |

Israel |

Observational comparison study |

100 Consecutive adult ED patients |

Emergency department |

GPT-4 LLM; ESI triage assignments |

GPT-4 assigned lower median ESI (more severe) compared to human evaluators, indicating overestimation of severity |

|

[A11] |

Tu et al. (2025) |

Multi-national |

Benchmarking study (MIMIC dataset) |

2,000 Cases from MIMIC dataset |

Mixed clinical settings (retrospective dataset) |

LLMs and retrieval-augmented generation workflows |

RAG improved safety and reliability of recommendations in benchmarking tasks |

|

[A12] |

Ho et al. (2025) |

USA |

Vignette evaluation |

45 Clinical vignettes |

Pediatric emergency department (simulated) |

GPT-4, Gemini, Claude; pediatric ESI vignettes |

Model performance varied; demographic and severity factors influenced accuracy |

|

[A13] |

Awad et al. (2025) |

Israel |

Simulation study |

32 ICU nurses |

Intensive care unit (simulation) |

Generative AI models; diagnostic interactions |

Demonstrated diagnostic synergies and highlighted limitations informing trust and appropriate reliance on AI |

|

[A14] |

Hassan and El-Ashry (2024) |

Australia |

Comparative analysis |

60 Youth mental health cases |

Mental health emergency triage |

ChatGPT-4; triage decision analysis |

ChatGPT showed potential but clinicians outperformed in nuanced assessments; governance concerns raised |

|

[A15] |

Lin et al. (2025) |

Taiwan |

National cross-sectional survey |

312 Registered nurses (national sample) |

Multiple clinical settings |

ChatGPT; AI literacy survey; training needs assessment |

Formal training rate (15%), preparedness (33%), interest in education (89%), competency gaps identified |

|

[A16] |

Paslı et al. (2024) |

South Korea |

System development and evaluation |

Asclepius dataset and clinician evaluator |

KTAS ED triage system |

Llama-3-70b base LLM multi-agent CDSS (CrewAI, Langchain) |

High accuracy in triage decisions; demonstrated multi-agent potential for Korean triage adaptation |

|

[A17] |

Masanneck et al. (2024) |

USA |

Comparative evaluation |

1 |

124 ED triage cases |

Emergency department |

ChatGPT-4 vs. standard triage protocols |

|

[A18] |

Saad et al. (2025) |

USA |

Mixed methods formative study |

Community nurses (simulation cases) |

Community nursing simulation |

Generative AI models (ChatGPT/LLMs); care planning |

Insights into diagnostic synergies and areas for refinement for care planning with LLM assistance |

|

[A19] |

Han et al. (2024) |

South Korea |

System development with clinician feedback |

Clinical evaluators and dataset |

KTAS ED triage |

Llama-3 multi-agent CDSS for Korean triage |

Demonstrated feasibility and clinician-level performance in simulated triage tasks |

|

[A20] |

Thotapalli et al. (2025) |

Israel |

Simulation study |

32 ICU nurses |

Critical care simulation center |

Multiple generative AI/LLM types; diagnostic confidence measures |

Observed differences in diagnostic suggestions; highlights for confidence calibration in clinical simulations |

|

[A21] |

Bauer et al. (2020) |

USA |

Analytic study of EHR and prospective evaluations |

EHR datasets and healthcare worker assessments |

Clinical documentation and workflow tasks |

ChatGPT and GPT-4 tested for clinical tasks |

High classification performance but risks (factual errors, privacy) impacting workflow |

|

[A22] |

Huang et al. (2025) |

Taiwan |

Descriptive simulation study |

Nursing students (pediatric simulation) |

Nursing education simulation in Taiwan |

ChatGPT models tested in simulation assessments |

ChatGPT performance varied; students generally outperformed models in most areas |

|

[A23] |

Nashwan and Hani (2023) |

USA |

Feasibility evaluation |

EHR datasets and hypothetical assessments |

Mobile and clinical assistant environments |

ChatGPT and GPT-4 models |

Demonstrated strengths but flagged errors and privacy issues affecting feasibility for mobile home use |

Table 2.Summary of Quality Assessments of Included Studies (N=23)

|

Study No. |

Assessment tool |

Overall quality |

Key limitations*

|

|

A1 |

NOS-CS |

Good (7/9) |

Vignette limitations; simulation-based; single-center; limited external validity |

|

A2 |

NOS-CS |

Excellent (8/9) |

Multi-center but limited sample size (n=32); NICU-specific focus |

|

A3 |

ROBINS-I |

Low risk |

Preprint status; retrospective design; single-center; computational complexity |

|

A4 |

ROBINS-I |

Low risk |

Retrospective design; no patient outcomes; Korean context only; model version dependency |

|

A5 |

ROBINS-I |

Low-moderate risk |

Preprint status; dataset-based evaluation; limited real-world validation |

|

A6 |

Modified NOS |

Good (7/9) |

Simulation limitations; generalizability concerns to real ICU practice; automation bias risk |

|

A7 |

Modified NOS |

Moderate (6/9) |

Small sample; single-site; limited methodological detail; scalability concerns |

|

A8 |

CASP |

High quality |

Single country (Saudi Arabia); limited transferability; very specific NICU context |

|

A9 |

ROBINS-I |

Low risk |

ICU clinicians not nurses only; simulation-based tasks; voice recognition accuracy |

|

A10 |

ROBINS-I |

Low-moderate risk |

Observational design; single-center; no patient outcomes; severity overestimation |

|

A11 |

Modified NOS |

Good (7/9) |

Implementation study; hallucination concerns noted; limited validation; need RAG |

|

A12 |

NOS-CS |

Good (7/9) |

Vignette limitations; pediatric focus only; limited generalizability; equity concerns |

|

A13 |

NOS-CS |

Excellent (8/9) |

Self-report bias; cross-sectional design; trust measurement challenges |

|

A14 |

CASP |

High quality |

Very small sample (n=10); nurse leaders only; limited generalizability |

|

A15 |

NOS-CS |

Excellent (8/9) |

Self-report bias; cross-sectional design; Taiwan context; competency gaps |

|

A16 |

ROBINS-I |

Low risk |

Single-center; Turkish context; no patient outcomes; observational design |

|

A17 |

ROBINS-I |

Low-moderate risk |

Comparative evaluation; dataset-based; limited clinical validation; acuity variation |

|

A18 |

Modified NOS |

Good (7/9) |

Simulation limitations; community nursing focus; may not transfer to acute care |

|

A19 |

Modified NOS |

Moderate (6/9) |

System development study; dataset-based; limited clinical validation; needs real-world testing |

|

A20 |

ROBINS-I |

Low-moderate risk |

Youth mental health focus only; limited generalizability; small sample; governance concerns |

|

A21 |

NOS cohort |

Good (7/9) |

Before-after design; automation not LLM-based; single-unit implementation |

|

A22 |

Modified NOS |

Good (7/9) |

Nursing students not practicing nurses; simulation-based; education focus |

|

A23 |

Modified NOS |

Moderate (5/9) |

Demonstration study; limited empirical data; oncology-specific; needs validation |

Table 3.Effects of Generative AI Technologies on Nursing Practice: Benefits, Challenges, and Risks (N=23)

|

Study No. |

AI technology type |

Aspects of nursing decision-making impacted |

Reported benefits and positive impacts |

Challenges, limitations, and risks |

|

A1 |

ChatGPT (GPT-3.5) |

Clinical assessment and diagnosis in emergency scenarios |

11.3-fold faster response time (45 sec vs. 8.5 min); comprehensive differential diagnosis generation |

Indecisiveness in initial assessments; appropriateness 29% lower than experts; 35% more unnecessary tests; over-conservative tendency |

|

A2 |

ChatGPT-4 and Claude-2.0 |

Neonatal clinical decision support and management |

High diagnostic appropriateness (94-98%); Claude-2.0 outperformed ChatGPT-4 in accuracy and speed |

Limitations in diagnostic specificity; therapeutic recommendations less reliable; need NICU-specific validation |

|

A3 |

MECR-RAG (DeepSeek-V3) |

Emergency triage decision-making with RAG |

Improved agreement (QWK 0.902) and accuracy (0.802); reduced over-triage; improved consistency |

Retrospective evaluation only; dependency on quality of retrieved evidence; computational complexity |

|

A4 |

Multiple LLMs (GPT-4o, Gemini, DeepSeek) |

Non-critical emergency triage (Korean language) |

Gemini 2.5 flash highest accuracy (73.8%); few-shot prompting improved performance; Korean feasibility |

Model performance varied significantly by version; limited to non-critical cases; requires ongoing validation |

|

A5 |

LLMs with RAG workflow |

Clinical decision support for triage, referral, and diagnosis |

RAG workflow improved reliability vs. prompt-only LLMs; personalized diagnostic suggestions; safer evidence-based reasoning |

Dataset-based benchmarking limits real-world applicability; dependency on knowledge base quality and currency |

|

A6 |

Multiple generative AI/LLM types |

ICU diagnostic reasoning and clinical case analysis |

Diagnostic synergies between AI and nurses; identification of rare conditions; differences across model types |

Simulation-based limitations; generalizability concerns to real ICU practice; risk of automation bias |

|

A7 |

ChatGPT-based LLM (A+ Nurse) |

Nursing documentation efficiency |

Documentation time reduced from ~15 to ~5 minutes per patient; maintained record quality; positive usability |

Single-site implementation; limited detail on accuracy validation; scalability concerns |

|

A8 |

Generative AI for decision support |

Clinical decision-making in high-risk NICUs |

AI enhancing clinical judgment; support for complex decision scenarios; workflow efficiency gains |

Requires human validation; evolving role boundaries; trust issues (only 34% high trust); liability concerns |

|

A9 |

Voice information and documentation system |

ICU documentation and information retrieval |

Significantly faster task completion than PDMS and paper; fewer errors; improved workflow efficiency |

ICU clinicians (not nurses only) in sample; voice recognition accuracy concerns; learning curve |

|

A10 |

GPT-4 LLM |

Emergency triage acuity assessment |

High agreement with clinician ESI assignments (Cohen's k ~0.899); rapid processing of patient data |

GPT-4 assigned lower median ESI (more severe) than human evaluators, indicating overestimation of severity |

|

A11 |

Generative LLM (nursing information system) |

Nursing handover documentation |

>99% documentation time reduction; enhanced clinical data integration across hospitals; improved work efficiency |

Occasional hallucinations when processing vital sign inputs; need for comparative analyses and RAG approaches |

|

A12 |

GPT-4, Gemini, Claude |

Pediatric emergency severity index prediction |

Multiple models available for comparison; demonstrated potential for pediatric triage support |

Model performance varied; demographic and severity factors influenced accuracy; equity concerns; pediatric-specific validation needed |

|

A13 |

AI-CDSS |

ICU nurses' trust, reliance, and decision regret |

Higher AI-CDSS reliance correlated with lower decision regret; trust in AI moderated emotional outcomes |

Self-report bias; cross-sectional design limits causal inference; trust calibration issues remain |

|

A14 |

Various AI tools in ICU |

AI governance, implementation, and ethical oversight |

Recognition of benefits in task automation; awareness of need for governance frameworks |

Concerns: overreliance, workflow adaptation, algorithmic bias, ethical accountability; need for transparency and training |

|

A15 |

ChatGPT |

AI literacy, training needs, and technology acceptance |

High perceived future role for AI; interest in education/training (89%); recognition of potential benefits |

Formal training rate only 15%; preparedness only 33%; concerns about accuracy and regulation; competency gaps |

|

A16 |

GPT-4 triage prompts |

Emergency department triage decision accuracy |

Almost perfect agreement with clinician assessment (Cohen's k ~0.899); high predictive performance |

Single-center study; Turkish context may limit generalizability; no patient outcome data |

|

A17 |

Multiple LLMs vs. clinicians |

Emergency medicine triage performance comparison |

Comparative performance metrics across models and humans; LLMs can inform untrained staff |

Performance varies by model and triage category; limited clinical validation; need for ongoing evaluation |

|

1A8 |

Generative LLM models |

Community nursing diagnostic reasoning and care planning |

Diagnostic synergies in community settings; implications for mobile/home health workflows; simulation training value |

Simulation-based limitations; community nursing focus may not transfer to acute care; limited real-world validation |

|

A19 |

Llama-3-70b multi-agent CDSS |

Korean KTAS-based triage and treatment planning |

High accuracy in triage decisions; demonstrated multi-agent potential; Korean language adaptation successful |

System development study; limited clinical validation; dataset-based evaluation; need for prospective real-world testing |

|

A20 |

ChatGPT-4 |

Youth mental health emergency triage |

ChatGPT showed potential for triage support; rapid processing of mental health crisis scenarios |

Clinicians outperformed ChatGPT in nuanced assessments; governance concerns; youth mental health specificity limits generalizability |

|

A21 |

Automated data entry tool (device-to-EHR) |

Vital sign documentation and data transfer automation |

Data errors decreased from ~20% to 0%; data transfer time reduced by 5 min-2 hr per event; improved job satisfaction |

Automation not LLM-based (pre-generative AI era); before-after design limits causal inference; single-unit implementation |

|

A22 |

ChatGPT models |

Pediatric simulation-based nursing education and assessment |

ChatGPT performance comparable in some simulation rounds; educational value for nursing students |

Nursing students (not practicing nurses); students generally outperformed models; simulation-based limitations |

|

A23 |

LLM-based care plan generation tools |

Oncology nursing care planning and documentation |

LLMs assist in care plan generation; support workflow efficiency; demonstrated feasibility in oncology context |

Demonstration study with limited empirical data; oncology-specific focus; need for validation across settings |

REFERENCES

- 1. Topol EJ. High-performance medicine: the convergence of human and artificial intelligence. Nature Medicine. 2019;25:44-56. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-018-0300-7

- 2. Rajkomar A, Dean J, Kohane I. Machine learning in medicine. New England Journal of Medicine. 2019;380(14):1347-1358. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1814259

- 3. Vaswani A, Shazeer N, Parmar N, Wallach H, Fergus R, Vishwanathan S, et al. Machine learning in medicine. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 30 (NIPS 2017). 2017;5998-6008.

- 4. Brown TB, Mann B, Ryder N, Subbiah M, Kaplan JD, Dhariwal P, et al. Language models are few-shot learners. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems. 2020;33:1877-901.

- 5. OpenAI. GPT-4 technical report. arXiv. OpenAI. GPT-4 technical report. arXiv [Preprint]. 2023 [cited 2026 Jan 12]. Available from: https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2303.08774

- 6. Benner P. From novice to expert excellence and power in clinical nursing practice. American Journal of Nursing. 1984;84:(12):1479. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000446-198412000-00025

- 7. Thompson C, Stapley S. Do educational interventions improve nurses’ clinical decision making and judgement? A systematic review. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2011;48(7):881-893. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2010.12.005

- 8. O'Connor S, Yan Y, Thilo FJS, Felzmann H, Dowding D, Lee JJ. Artificial intelligence in nursing and midwifery: A systematic review. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2023;32(13-14):2951-2968. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.16478

- 9. Robert N. How artificial intelligence is changing nursing. Nursing Management. 2019;50(9):30-39. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NUMA.0000578988.56622.21

- 10. Buchanan C, Howitt ML, Wilson R, Booth RG, Risling T, Bamford M. Predicted influences of artificial intelligence on nursing education: scoping review. JMIR Nursing. 2021;4:(1):e23933. https://doi.org/10.2196/23933

- 11. Risling T, Martinez J, Young J, Thorp-Froslie N. Evaluating patient empowerment in association with eHealth technology: scoping review. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2017;19:(9):e329. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.7809

- 12. Beil M, Proft I, van Heerden D, Sviri S, van Heerden PV. Ethical considerations about artificial intelligence for prognostication in intensive care. Intensive Care Medicine Experimental. 2019;7:(Suppl 1):70. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40635-019-0286-6

- 13. Char DS, Shah NH, Magnus D. Implementing machine learning in health care - addressing ethical challenges. New England Journal of Medicine. 2018;378(11):981-983. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1714229

- 14. Price WN 2nd, Gerke S, Cohen IG. Potential liability for physicians using artificial intelligence. JAMA. 2019;322(18):1765-1766. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.15064

- 15. Reddy S, Allan S, Coghlan S, Cooper P. A governance model for the application of AI in health care. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2020;27(3):491-497. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocz192

- 16. Aiken LH, Clarke SP, Sloane DM, Sochalski J, Silber JH. Hospital nurse staffing and patient mortality, nurse burnout, and job dissatisfaction. JAMA. 2002;288(16):1987-1993. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.288.16.1987

- 17. Cho E, Lee NJ, Kim EY, Hong KJ, Kim Y. Nurse staffing levels and proportion of hospitals and clinics meeting the legal standard for nurse staffing for 1996-2013. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing Administration. 2016;22(3):209-219. https://doi.org/10.11111/jkana.2016.22.3.209

- 18. Kelly CJ, Karthikesalingam A, Suleyman M, Corrado G, King D. Key challenges for delivering clinical impact with artificial intelligence. BMC Medicine. 2019;17:(1):195. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-019-1426-2

- 19. Meskó B, Topol EJ. The imperative for regulatory oversight of large language models (or generative AI) in healthcare. NPJ Digital Medicine. 2023;6:(1):120. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-023-00873-0

- 20. Lee P, Bubeck S, Petro J. Benefits, limits, and risks of GPT-4 as an AI chatbot for medicine. New England Journal of Medicine. 2023;388(13):1233-1239. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsr2214184

- 21. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

- 22. Sterne JA, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4898. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l4898

- 23. Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, Savović J, Berkman ND, Viswanathan M, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016;355:i4919. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i4919

- 24. Wells GA, Shea B, O'Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses [Internet]. Ottawa: Ottawa Hospital Research Institute; 2013 [cited 2026 Jan 12]. Available from: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp

- 25. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP). CASP qualitative checklist [Internet]. Oxford: CASP; 2018 [cited 2026 Jan 12]. Available from: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/

- 26. Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, Petticrew M, Arai L, Rodgers M, et al. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. Lancaster: ESRC Methods Programme; 2006.

- 27. Cvach M. Monitor alarm fatigue: an integrative review. Biomedical Instrumentation & Technology. 2012;46(4):268-277. https://doi.org/10.2345/0899-8205-46.4.268

- 28. Saban M, Dubovi I. A comparative vignette study: Evaluating the potential role of a generative AI model in enhancing clinical decision-making in nursing. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2025;81(11):7489-7499. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.16101

- 29. Levin C, Kagan T, Rosen S, Saban M. An evaluation of the capabilities of language models and nurses in providing neonatal clinical decision support. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2024;156:104771. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2024.104771

- 30. Wong HV, Wong TK. Multi-evidence clinical reasoning with retrieval-augmented generation (MECR-RAG) for emergency triage: retrospective evaluation study. JMIR Preprints [Preprint]. 2025 [cited 2026 Jan 12]. Available from: https://doi.org/10.2196/preprints.82026

- 31. Lee S, Jung S, Park JH, Cho H, Moon SW, Ahn S. Performance of ChatGPT, Gemini and DeepSeek for non-critical triage support using real-world conversations in emergency department. BMC Emergency Medicine. 2025;25:(1):176. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12873-025-01337-2

- 32. Gaber F, Shaik M, Allega F, Bilecz AJ, Busch F, Goon K. Evaluating large language model workflows in clinical decision support for triage and referral and diagnosis. npj Digital Medicine. 2025;8:(1):263. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-01684-1

- 33. Levin C, Suliman M, Naimi E, Saban M. Augmenting intensive care unit nursing practice with generative AI: a formative study of diagnostic synergies using simulation-based clinical cases. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2024;34(7):2898-2907. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.17384

- 34. Chen CJ, Liao CT, Tung YC, Liu CF. Enhancing healthcare efficiency: Integrating ChatGPT in nursing documentation. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics. 2024;316:851-852. https://doi.org/10.3233/SHTI240545

- 35. Alruwaili AN, Alshammari AM, Alhaiti A, Elsharkawy NB, Ali SI, Elsayed Ramadan OM. Neonatal nurses' experiences with generative AI in clinical decision-making: a qualitative exploration in high-risk NICUs. BMC Nursing. 2025;24:386. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-025-03044-6

- 36. Peine A, Gronholz M, Seidl-Rathkopf K, Wolfram T, Hallawa A, Reitz A, et al. Standardized comparison of voice-based information and documentation systems to established systems in intensive care: crossover study. JMIR Medical Informatics. 2023;11:e44773. https://doi.org/10.2196/44773

- 37. Haim GB, Saban M, Barash Y, Cirulnik D, Shaham A, Eisenman BZ, et al. Evaluating large language model-assisted emergency triage: a comparison of acuity assessments by GPT-4 and medical experts. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2024 Nov 28 [Epub];https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.17490

- 38. Tu YH, Chang TH, Lo YS. Generative AI-assisted nursing handover: enhancing clinical data integration and work efficiency. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics. 2025;329:1928-1929. https://doi.org/10.3233/SHTI251283

- 39. Ho B, Meng L, Wang X, Butler R, Park J, Ren D. Evaluation of generative artificial intelligence models in predicting pediatric emergency severity index levels. Pediatric Emergency Care. 2025;41(4):251-255. https://doi.org/10.1097/pec.0000000000003315

- 40. Awad NH, Aljohani W, Yaseen MM, Awad WH, Abou Elala RA, Ashour HM. When machines decide: exploring how trust in ai shapes the relationship between clinical decision support systems and nurses' decision regret: a cross-sectional study. Nursing in Critical Care. 2025;30:(5):e70157. https://doi.org/10.1111/nicc.70157

- 41. Hassan EA, El-Ashry AM. Leading with AI in critical care nursing: challenges, opportunities, and the human factor. BMC Nursing. 2024;23:752. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-024-02363-4

- 42. Lin HL, Liao LL, Wang YN, Chang LC. Attitude and utilization of ChatGPT among registered nurses: a cross-sectional study. International Nursing Review. 2025;72:(2):e13012. https://doi.org/10.1111/inr.13012

- 43. Paslı S, Şahin AS, Beşer MF, Topçuoğlu H, Yadigaroğlu M, İmamoğlu M. Assessing the precision of artificial intelligence in ED triage decisions: insights from a study with ChatGPT. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2024;78:170-175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2024.01.037

- 44. Parasuraman R, Manzey DH. Complacency and bias in human use of automation: an attentional integration. Human Factors. 2010;52(3):381-410. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018720810376055

- 45. Skitka LJ, Mosier KL, Burdick M. Does automation bias decision-making? International Journal of Human-Computer Studies. 1999;51(5):991-1006. https://doi.org/10.1006/ijhc.1999.0252

- 46. Lyell D, Coiera E. Automation bias and verification complexity: a systematic review. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2017;24(2):423-431. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocw105

- 47. Bauer JC, John E, Wood CL, Plass D, Richardson D. Data entry automation improves cost, quality, performance, and job satisfaction in a hospital nursing unit. JONA: The Journal of Nursing Administration. 2020;50(1):34-39. https://doi.org/10.1097/NNA.0000000000000836

- 48. American Nurses Association. The ethical use of artificial intelligence in nursing practice: position statement [Internet]. Silver Spring, MD: American Nurses Association; 2022 [cited 2026 Jan 12]. Available from: https://www.nursingworld.org/globalassets/practiceandpolicy/nursing-excellence/ana-position-statements/the-ethical-use-of-artificial-intelligence-in-nursing-practice_bod-approved-12_20_22.pdf

Appendix

Appendix 1.

List of Included Studies

A1. Saban M, Dubovi I. A comparative vignette study: evaluating the potential role of a generative AI model in enhancing clinical decision-making in nursing. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2025;81(11):7489-7499.

https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.16101

A2. Levin C, Kagan T, Rosen S, Saban M. An evaluation of the capabilities of language models and nurses in providing neonatal clinical decision support. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2024;156:104771.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2024.104771

A3. Wong HV, Wong TK. Multi-evidence clinical reasoning with retrieval-augmented generation (MECR-RAG) for emergency triage: retrospective evaluation study. JMIR Preprints [Preprint]. 2025 [cited 2026 Jan 12]. Available from:

https://doi.org/10.2196/preprints.82026

A4. Lee S, Jung S, Park JH, Cho H, Moon SW, Ahn S, et al. Performance of ChatGPT, Gemini and DeepSeek for non-critical triage support using real-world conversations in emergency department. BMC Emergency Medicine. 2025;25(1):176.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12873-025-01337-2

A5. Gaber F, Shaik M, Allega F, Bilecz AJ, Busch F, Goon K, et al. Evaluating large language model workflows in clinical decision support for triage and referral and diagnosis. npj Digital Medicine. 2025;8(1):263.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-01684-1

A6. Levin C, Suliman M, Naimi E, Saban M. Augmenting intensive care unit nursing practice with generative AI: a formative study of diagnostic synergies using simulation-based clinical cases. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2024;34(7):2898-2907.

https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.17384

A7. Chen CJ, Liao CT, Tung YC, Liu CF. Enhancing healthcare efficiency: integrating ChatGPT in nursing documentation. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics. 2024;316:851-852.

https://doi.org/10.3233/SHTI240545

A8. Alruwaili AN, Alshammari AM, Alhaiti A, Elsharkawy NB, Ali SI, Elsayed Ramadan OM. Neonatal nurses' experiences with generative AI in clinical decision-making: a qualitative exploration in high-risk NICUs. BMC Nursing. 2025;24:386.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-025-03044-6

A9. Peine A, Gronholz M, Seidl-Rathkopf K, Wolfram T, Hallawa A, Reitz A, et al. Standardized comparison of voice-based information and documentation systems to established systems in intensive care: crossover study. JMIR Medical Informatics. 2023;11:e44773.

https://doi.org/10.2196/44773

A10. Haim GB, Saban M, Barash Y, Cirulnik D, Shaham A, Eisenman BZ, et al. Evaluating large language model‐assisted emergency triage: a comparison of acuity assessments by GPT‐4 and medical experts. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2024.

https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.17490

A11. Tu YH, Chang TH, Lo YS. Generative AI-assisted nursing handover: enhancing clinical data integration and work efficiency. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics. 2025;329:1928-1929.

https://doi.org/10.3233/SHTI251283

A12. Ho B, Meng L, Wang X, Butler R, Park J, Ren D. Evaluation of generative artificial intelligence models in predicting pediatric emergency severity index levels. Pediatric Emergency Care. 2025;41(4):251-255.

https://doi.org/10.1097/pec.0000000000003315

A13. Awad NH, Aljohani W, Yaseen MM, Awad WH, Abou Elala RA, Ashour HM. When machines decide: exploring how trust in ai shapes the relationship between clinical decision support systems and nurses' decision regret: a cross-sectional study. Nursing in Critical Care. 2025;30(5):e70157.

https://doi.org/10.1111/nicc.70157

A15. Lin HL, Liao LL, Wang YN, Chang LC. Attitude and utilization of ChatGPT among registered nurses: a cross-sectional study. International Nursing Review. 2025;72(2):e13012.

https://doi.org/10.1111/inr.13012

A16. Paslı S, Şahin AS, Beşer MF, Topçuoğlu H, Yadigaroğlu M, İmamoğlu M. Assessing the precision of artificial intelligence in ED triage decisions: insights from a study with ChatGPT. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2024;78:170-175.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2024.01.037

A17. Masanneck L, Schmidt L, Seifert A, Kölsche T, Huntemann N, Jansen R, et al. Triage performance across large language models, ChatGPT, and untrained doctors in emergency medicine: comparative study. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2024;26:e53297.

https://doi.org/10.2196/53297

A18. Saad O, Saban M, Kerner E, Levin C. Augmenting communitynursing practice with generative AI: a formative study of diagnostic synergies using simulation-based

clinical cases. Journal of Primary Care & Community Health. 2025;16:21501319251326663.

https://doi.org/10.1177/21501319251326663

A19. Han S, Choi W. Development of a large language model-based multi-agent clinical decision support system for Korean Triage and Acuity Scale (KTAS)-based triage and treatment planning in emergency departments. arXiv [Preprint]. 2024 [cited at 2026 Jan 15].

https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2408.07531

A20. Thotapalli S, Yilanli M, McKay I, Leever W, Youngstrom E, Harvey‐Nuckles K, et al. Potential of ChatGPT in youth mental health emergency triage: Comparative analysis with clinicians. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences Reports. 2025;4(3):e70159.

https://doi.org/10.1002/pcn5.70159

A21. Bauer JC, John E, Wood CL, Plass D, Richardson D. Data entry automation improves cost, quality, performance, and job satisfaction in a hospital nursing unit. JONA: The Journal of Nursing Administration. 2020;50(1):34-9.

https://doi.org/10.1097/NNA.0000000000000836

A22. Huang HM, Shu SH. The effectiveness of ChatGPT in pediatric simulation-based tests of nursing courses in Taiwan: A descriptive study. Clinical Simulation in Nursing. 2025;102:101732.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecns.2025.101732

A23. Nashwan AJ, Hani SB. Enhancing oncology nursing care planning for patients with cancer through Harnessing large language models. Asia-Pacific Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2023;10(9):100277.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apjon.2023.100277